The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) issued its annual report, EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) 2021. The report documents terrorism events and updates, and closely observes the terrorism situation, terrorist attacks, and arrests in the EU in 2020. It thereby profiles the phenomenon of terrorism in Europe quantitively and qualitatively to decision-makers. The report shows that six EU Member States reported 57 completed, failed, and foiled terrorist attacks in 2020, resulting in 21 deaths as opposed to 2019, which witnessed 119 attacks, killing 10 people.

Militant terrorism

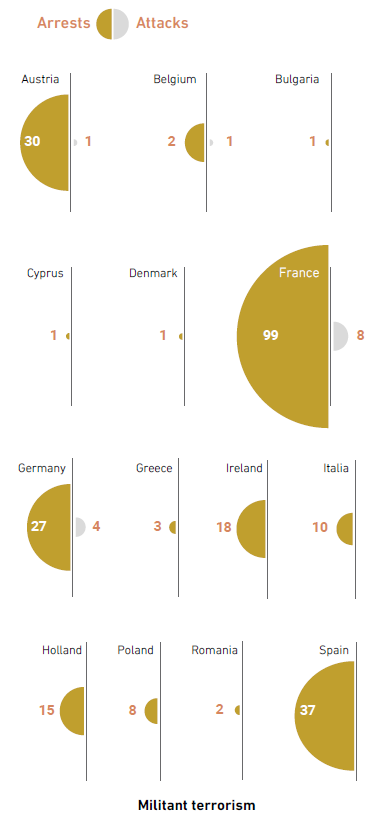

The TE-SAT report addresses militant terrorism as “Jihadist Terrorism”, referring to terrorism undertaken by members of the Islamic State (IS) or other terrorist groups, or individuals adopting their beliefs and are inspired by them. In 2020, three EU Member States—Austria, France, and Germany—witnessed ten completed jihadist terrorist attacks, resulting in 12 deaths and more than 47 casualties. Meanwhile, Belgium, France, and Germany witnessed four foiled attacks. In the UK, three jihadist attacks were completed and two were foiled. Switzerland also faced two attacks. This means that the total of completed jihadist terrorist attacks in Europe—EU, Switzerland, and the UK (before the Brexit deal is completed)—in 2020 more than doubled the number of attacks in 2019.

Shootings, stabbings, or hit-and-run operations targeting civilians in public places were the most frequent types of jihadist attacks in the EU, Switzerland, and the UK. All jihadist attackers were males aged between 18 and 33.

The family background or place of birth of perpetrators varied significantly; four completed jihadist attacks were perpetrated by individuals holding EU citizenship, while perpetrators of five attacks entered the EU as asylum seekers or irregular migrants. All completed attacks were perpetrated by individuals acting alone (lone wolves). It also turned out that a number of suspects arrested in 2020 contacted followers of terrorist groups outside the EU online.

In 2020, 254 individuals, 87% being male, were arrested on suspicion of committing jihadist offences, affiliating to terrorist groups, propaganda dissemination for terrorist views, planning terrorist acts, or facilitating and financing terrorism. Accordingly, the total of arrests on suspicion of terrorism in EU Member States dropped by more than half as opposed to previous years.

EU Member States are yet concerned about recruitment in prison and the threat posed by released IS prisoners and al-Qaeda supporters. Released prisoners were involved in five terrorist attacks carried out in Austria, Germany, and the UK in 2020. However, overall recidivism among terrorism convicts in Europe is still relatively low.

Recruitment to terrorist groups of al-Qaeda and IS has taken place via online networks, especially via encrypted messaging, or through relationships offline, such as friendships or family relations. These terrorist groups and others outside the EU have also promoted extremist content online for their members and supporters in Europe including elements of incitement to individual attacks in Western countries. However, the quantity and quality of propaganda produced by official IS media outlets decreased significantly in 2020.

Through its propaganda, IS emphasized its military successes outside Syria and Iraq in an attempt to prove their continued control of territory. It also appealed to its fighters and supporters to free Muslim prisoners, including those in Europe, and called for lone-wolf attacks. Moreover, IS sought to reestablish its online networks after its Telegram platform has been taken down in November 2019. Meanwhile, al-Qaeda continued to maintain a sustained propaganda presence online in 2020 through its media outlets to comment on current affairs, and publicly affirm the bond between its regional affiliates.

Very few attempts by supporters of IS, al-Qaeda to travel to conflict zones were reported in 2020. 20%-50% of all travelers to Iraq and Syria were reported to have returned since the beginning of the conflict. Given the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, travel restrictions affected the return of foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) to Europe. However, a small number of returnees to EU Member States was reported.

Right-wing (RW) terrorism

Three EU Member States witnessed four terrorist attacks perpetrated by right-wing extremism, one of which resulted in nine deaths in Germany. Another attack was foiled in Germany; three of the four perpetrators (including one female) were citizens of the country where the attack took place or was planned.

34 individuals were arrested in eight EU Member States on suspicion of involvement in right-wing terrorist activity, being affiliated to terrorist groups, plotting or preparing for attacks, or possession of weapons. Most suspects were male with an average age of 38, and nationals of the country in which they were arrested.

It was alarming that some of the suspects were minors at the time of their arrest, and mostly linked to transnational violent online communities with varying degrees of organization, that adopt the concept of “leaderless resistance”.

Right-wing terrorism and extremism have continued to establish heterogeneous sets of ideologies and political objectives, ranging from lone individuals linked to extremist online communities to hierarchical organizations. Many EU Member States successfully dismantled or banned violent Neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups that call for attacks targeting Muslims or Jews, the destruction of the democratic order, and the establishment of new communities based on racist ideology. Some of these groups financed their activities through criminal means, including drug trafficking.

Combat training and access to weapons are increasing the capabilities of right-wing extremists to commit acts of violence. Right-wing extremists tend to be highly interested in paramilitary training, sometimes outside the EU, especially in Russia.

The increasing public awareness of climate and ecological crises led right-wing extremists to increasingly promote eco-fascist views. Eco-fascism attributes these crises to overpopulation, immigration and the democratic systems’ failure to address them. In 2020, they increasingly used video games to disseminate right-wing terrorist and extremist propaganda, particularly among young people. They also continued to use various online platforms, social media, and messaging services.

Left-wing and anarchist (LWA) terrorism

All attacks and most plots attributed to left-wing and anarchist groups occurred in Italy. One attack of the sort was foiled; however, these attacks often caused damage to private and public property (such as financial institutions and governmental buildings).

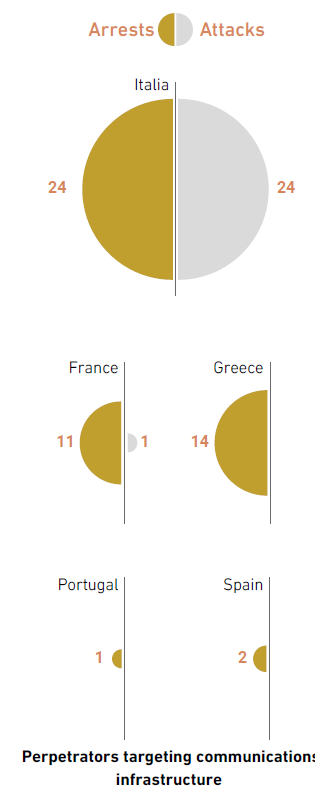

The number of arrests related to left-wing and anarchist terrorism, only 52, decreased by more than half compared to 2019, due to the decreased number of arrests in Italy (24 in 2020, compared to 98 in 2019). However, it remained significantly higher than in 2018 (34). Suspects were arrested in Italy (24), Greece (14), France (11), Spain (2), and Portugal (1). 70% of the arrestees were male. The average age was 40 for men, and 34 for women.

Left-wing and anarchist extremism continued to pose a threat to public order in a number of EU Member States. The Internet continued to be the main means for left-wing and anarchist terrorists to claim responsibility for attacks and disseminate propaganda and recruitment.

Dissidents in Ireland and SpainIn 2020, the threat posed by Dissident Republican (DR) groups to Northern Ireland remained unchanged at ‘Severe’, as specified by the UK, meaning that an attack is highly likely. Although a number of DR groups adopting anti-British sentiment and beliefs evolved following the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the current threat mainly stems from two DR groups: the new Irish Republican Army (NIRA) and the Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA). Despite the suppression of the activities of these groups due to the imposed government restrictions during 2020 to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, they have, initially, returned to their previous levels of operational activity. Their attacks involved the use of firearms or small improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as well as larger and more destructive devices, such as the deployment of vehicle-borne IEDs and explosively formed projectiles.

The DR support is practically confined in Ireland and Northern Ireland, especially through funding and arms supply. Their terrorist activity currently falls under the spotlight in international media because of the Irish border issue after Brexit. Spain, on the other hand, witnessed an increased violent separatist activity in 2020 as opposed to the previous year despite the separatist groups calls for alternative non-violent initiatives. Separatists seemed motivated by more violent narratives and consequently carried out a number of violent acts, reflecting a shift to more aggressive tactics on the Spanish separatist scene. Separatist militants carried out a total of nine attacks that were classified as terrorism, mostly to support ETA prisoners on hunger strike.

Separatist ETA remained inactive in the Basque Region in 2020, ceasing any terrorist acts since 2009. Even though ETA dissolution and disarmament has been declared in 2018, three ETA arms caches were found in 2020, confining various types of arms and explosives. In addition, 12 people were arrested on charges related to separatist terrorism in Spain, including one ETA member who was arrested for involvement in the assassination of a politician in 2001 and three more ETA members arrested for being members of ETA terrorist organization and for possession of explosives for terrorist purposes.

Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK)

The Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, ‘Kurdistan Workers’ Party’) continued to avoid carrying out attacks on EU soil, but remained active in non-violent mobilization in order to provide financial and logistical support to its operatives in Turkey and neighboring countries using legally recognized entities, such as Kurdish associations.

A number of European countries reported that the pandemic negatively affected overall PKK activity due to travel and gathering restrictions that limited the group’s protest activities and fundraising. The PKK organized demonstrations to promote its goals and to protest against Turkish military interventions in Syria and policies in relation to the Kurdish issue. Most PKK activity was peaceful, however some actions involved violent riots due to confrontation with Turkish nationalist counter-protesters. Austria and the Netherlands, for instance, reported tensions between PKK and Grey Wolves (an Ultra-nationalist Turkish group) members during or after PKK events.

A number of PKK members travelled from Europe to Syria or Iraq to join the Kurdish forces. Belgium reported that a total of nine Belgians of Kurdish origin joined the conflict in Syria and Iraq via PKK recruitment networks. Five of them have returned and one has been killed. Similarly, a man was sentenced in the UK to one year in prison for attending PKK terrorist training camps in Iraq.

State-sponsored terrorism

In addition to terrorist acts committed by home-grown extremists or foreign terrorist organizations, EU Member States also expressed concern about terrorist attacks in the EU committed on behalf of foreign governments. Such acts may increase tensions between different ethnic and national communities in the EU. Germany uncovered intelligence services of foreign countries spying on opposition members in Germany. In recent years, assassinations have shown that these activities can potentially lead to state-sponsored acts of terrorism.

Assassinations and attempted assassinations have targeted Russian citizens of Chechen origin in several EU Member States in recent years. In late January 2020, a Chechen dissident was found murdered in a hotel in Lille, France. On 4 July 2020, an ethnic Chechen was killed near Vienna, Austria. In August 2019, the German Federal Public Prosecutor-General indicted a Russian citizen with the murder of a Georgian citizen of Chechen origins in Berlin. The indictment posited that the crime was committed on behalf of government agencies of the Russian Federation.

Iran has maintained operatives in Europe who might be ordered to perpetrate terrorist attacks. Austria arrested an Iranian citizen in October 2020 on suspicion of membership of Niru-ye Qods (Quds Force, ‘Jerusalem force’), the special operations force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). In addition, an Iranian diplomat and three Belgians of Iranian origin were sentenced to up to 20 years imprisonment in Belgium in February 2021 for an attempted attack on an Iranian opposition meeting near Paris. In April 2020, Germany banned the activities of Iranian-backed Lebanese group Hizbullah in Germany. In June 2020, a Lebanese citizen was arrested in Austria on suspicion of membership of Hizbullah.

The COVID-19 pandemic and terrorism

It is still difficult to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on terrorism in 2020 and whether the notable decrease in arrests linked to various kinds of terrorist acts in the EU resulted from the pandemic. It is also difficult to attribute the changes in terrorist activity or the response to the pandemic. However, some violent acts and threats were clearly linked to the pandemic, including one failed right-wing extremist attack in Belgium that was motivated by opposition to the government’s COVID-19 measures. Czech authorties also arrested a Czech national for threatening a terrorist attack if restaurants and pubs were not reopened.

Due to the anti-COVID-19 restrictions on public life, opportunities to perpetrate terrorist attacks with a large number of victims declined, as many soft targets like museums, churches and stadiums were closed or only accessible to small numbers of people.

The measures taken by authorities to combat COVID-19 and the drop in international travel in 2020 temporarily restricted terrorists’ freedom of movement. The pandemic also limited opportunities for physical meetings among terrorists and extremists. In contrast, the crisis seems to have led to increased online networking among terrorists, and the increased time spent online has probably increased the consumption of terrorist propaganda. It was also observed that the pandemic led to the increase in right-wing extremist transnational activity online when physical meetings were restricted.

Terrorists and extremists of different ideologies tried to frame COVID-19 in line with their own narratives. IS, on the one hand, portrayed the pandemic as a punishment from God for his enemies, inciting the group’s followers to perpetrate attacks to take advantage of the increased vulnerability of anti-IS coalition countries. On the other hand, al-Qaeda interpreted the spread of the pandemic in Muslim-majority countries as a sign that people had abandoned true Islam, and appealed to Muslims to seek God’s mercy by liberating Muslim prisoners, providing for people in need, and supporting jihadist groups. Whereas, right-wing extremists exploited COVID-19 to support their narratives of accelerationism and conspiracy theories featuring anti-Semitism, and anti-immigration and anti-Islam rhetoric. Left-wing and anarchist extremists also incorporated criticism of government measures to combat the pandemic into their radical narratives.

EU Member States expressed their concern about possible security implications of the COVID-19 pandemic at the individual level. There is a risk posed by the situation created by the pandemic where it acts as an additional stress factor for radicalized individuals with mental health problems. This may lead lone wolves to turn to violence sooner than they would under different circumstances. Effects of the pandemic that might potentially contribute to self-radicalization included: social isolation from family and friends as a result of temporary restrictions on the free movement of people; reduced job security and subsequent financial difficulties; dissatisfaction with anti-COVID measures; and the increasing misinformation online.

In general, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic and social crises have contributed to increased polarization in society, causing attitudes to harden and expressions of social dissatisfaction to increase. This environment allowed extremist groups to reach audiences beyond their traditional supporters.

Weaponry of terrorist attacks

Most terrorist attacks in 2020 were committed by simple means, including stabbing, vehicle ramming and arson. Firearms were used in the right-wing terrorist attack in Hanau, Germany on 19 February and the jihadist terrorist attack in Vienna on 2 November.

As in previous years, homemade explosives (HMEs) were still used in most terrorist operations suspected to be linked to IS, al-Qaeda, and other jihadist groups in 2020. Unlike in the past, triacetone triperoxide (TATP) is no longer the predominant type of explosives. The preferred method of operation in 2020 involved the use of simple low explosive mixtures under the restrictive EU regulation on the use or purchase of the previous TATP. However, attempts to acquire such explosives from certain EU Member States through online shops were observed.

The explosive materials employed by IS, al-Qaeda, and other jihadist terrorists in 2020 were either homemade or sourced from readily available commercial articles (e.g. pyrotechnics and cartridges). Consequently, most recovered improvised explosive devices (IEDs) were designed in the form of rudimentary pipe or pressure cooker bombs.

The level of activity concerning explosive-related attacks perpetrated by right-wing terrorism did not increase further compared to 2019. The methods still included the commission of arson and explosive attacks with simple improvised incendiary devices (IEDs) constructed with readily available materials. In addition, some incidents showed that right-wing terrorists were still interested in and capable of manufacturing more complex HMEs, such as TATP and nitroglycerine.

As in previous years, anarchist extremist groups used simple IIDs filled with flammable liquids/gases or IEDs filled with easily available explosive materials, such as pyrotechnic mixtures. Additionally, several parcel bomb campaigns were launched in 2020, mostly battery-powered IEDs hidden in postal packages or envelopes and equipped with incendiary or low explosive charges.

2020, as in the previous year, witnessed no terrorist attacks using chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) materials in EU Member States. Nevertheless, trials of cases involving the use of CBRN materials were concluded in 2020 or were ongoing at the time of writing the TE-SAT report. For example, the perpetrators of the 2018 Germany ricin plot were sentenced to 10 and 8 years in prison, respectively. Additionally, in other cases suspects were arrested for intention to purchase CBRN materials through the dark web.

Terrorism and crime

There is little evidence of systematic cooperation between criminals and terrorists in the EU despite the engagement of both in illegal means achieving their goals. Nevertheless, an overlap between organized crime groups and right-wing extremists, in particular with regard to weapons procurement and drug trafficking, has been observed. In January 2020, Spain arrested 16 members of the Spanish chapter of an international organization linked to drug trafficking and sexual exploitation of women. The group’s proceeds in Spain was used to finance its members’ activities in violent right-wing extremist groups, including football hooligans and neo-Nazi groups. Also, a transnational group trafficking weapons to drug-trafficking networks south of Spain was dismantled in late 2020, including a German citizen linked to right-wing extremist and neo-Nazi networks.

The connection linking Dissident Republican (DR) groups in Ireland and Northern Ireland (UK) to organized and nonorganized crime is well established. Traditionally, fundraising through extortion, weapons trafficking and excise fraud (including cigarettes, alcohol and fuel) has brought these groups into contact with organized criminals.

Criminals seeking profit often refrain from cooperating with terrorists to avoid drawing the attention of authorities towards their activities. Whereas individuals affiliated to terrorist networks were observed to have personal connections with non-organized crime. Moreover, there are indications that activities of IS, al-Qaeda, and other jihadist groups are partly financed through other crimes, such as robbery, extortion, drugs trafficking, money laundry, and human trafficking, particularly evidently among members of Chechen, Afghan, and West-Balkan communities. In some cases, it was observed that individuals experienced in facilitating terrorism have presented forged documents and small amounts of money.

Financing of terrorism

Sources of terrorist financing vary significantly. Terrorists rely on legal and illegal funds. Financing of terrorist organizations differs from financing of terrorist attacks committed by individual terrorists or small groups. Attacks by lone actors or small groups often use unsophisticated means that do not require large funds and, thus, might be self-funded by the perpetrators. Financing needs increase when the perpetrators intend to use firearms, explosives, or other more sophisticated attack methodologies.

Terrorist and extremist organizations need financial support to cover logistical needs like maintaining an infrastructure, recruitment, propaganda, and enhancing operational capacities. Such organizations can rely on their members for funding activities. For example, violent right-wing extremist organizations in Finland and Sweden finance their activities mainly through membership fees and donations from their members and supporters. Polish authorities observed that, in addition to collections from members, right-wing extremist groups fund their activities through legal private businesses run by members. Meanwhile, criminal activities of violent left-wing extremists are usually not very costly, and the networks’ financial resources mainly come from so-called support parties.

In Europe, funds are also raised for the activities of terrorist groups outside Europe through legal sources, such as money collections and donations, and illegal sources like drug trafficking. Ireland, for example, reported 17 arrests in 2020 in connection with financing of IS, al-Qaeda, and other jihadist terrorism.

It was reported that donations were collected in support of women and children detained in camps for former IS members and their families in northeast Syria. Switzerland, for example, filed a small number of criminal proceedings regarding terrorism financing involving family members of jihadist travelers sending financial support to their relatives in conflict zones. Sweden also noted that funds transferred to the conflict area in 2020 were primarily aimed at supporting individuals detained in camps or prisons. This type of financing is probably not illegal per se in Sweden, but there is a concern that it might contribute indirectly to Swedish citizens with conflict and combat experience returning to Sweden or a third country. Spain also observed that foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) in the conflict zone received funds to return to Europe. Consequently, even individuals were arrested for funding violent terrorists affiliated with IS in the conflict zone.

Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK) has continued fundraising by legal and illegal means in Europe, through fundraising campaigns, donations, extortion, and other organized criminal activities. In this context, Germany arrested numerous PKK affiliates for participating in coordinating annual fundraisers. Money generated in Europe is transferred to terrorists outside Europe through cash movement via couriers, front companies, bank transfer, the informal banking system known as hawala, and wiring (MoneyGram, Western Union).

The number of cases involving the misuse of new payment methods especially cryptocurrencies remained low in 2020. The potential for using cryptocurrency in terrorism finances, however, was demonstrated in August 2020, when the US Department of Justice announced the seizure of more than 300 cryptocurrency accounts used for terrorist financing campaigns

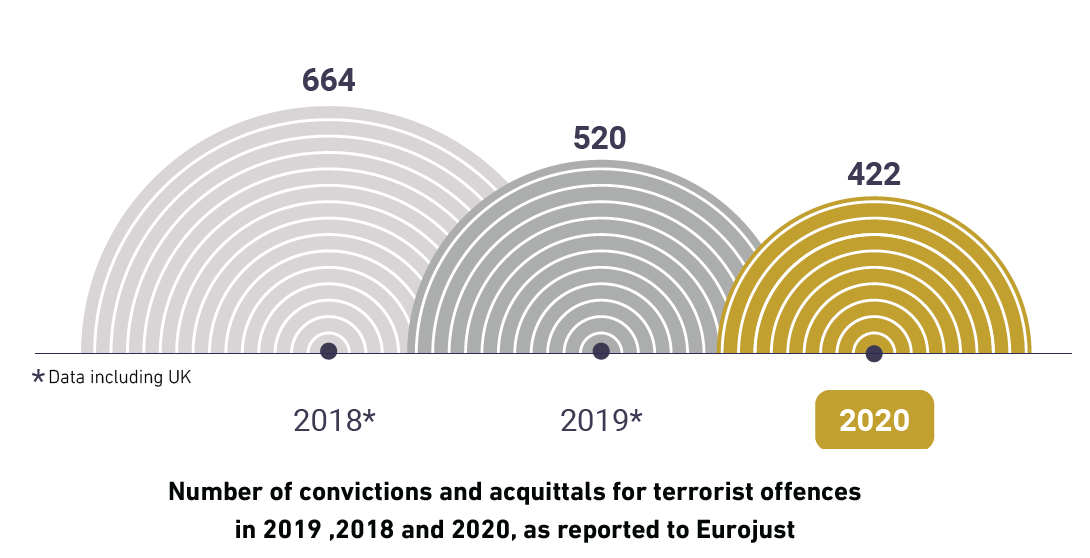

Convictions and penalties

EU Member States and Britain concluded trials resulting in nearly 422 convictions and acquittals. France, Germany and Belgium reported the highest number of convictions and acquittals for terrorist offences in 2020 (155, 67 and 52, respectively).

Some of the convictions and acquittals in 2020 reported by EU Member States are final, while others are pending judicial remedy, as appeals have been submitted by the prosecution, the defense counsel, or both. The average sentence for terrorism-related offences passed by EU Member States courts was eight years in prison, surpassing the average in 2019 (six years), the shortest sentence was three months, and the longest was for life.

Convictions and acquittals for left-wing and anarchist terrorism-related offences were the second largest type in the EU. As in previous years, the highest number of convictions and acquittals for separatist terrorism-related offences were pronounced in Spain. Courts in the Czechia, France, Germany and the Netherlands also heard cases of alleged offences linked to separatist terrorist organizations.

The number of convictions for right-wing terrorism increased in 2020 (11) compared to 2019 (6). Participation in the activities of a terrorist group, financing of terrorism, or training for terrorist purposes were among the most common offences dealt with in the court proceedings for terrorist offences concluded in 2020. Next came the dissemination of terrorist propaganda, incitement to terrorism, recruitment, complicity in the preparation and facilitation of terrorist offences. Some of the people who appeared before court on terrorism charges in 2020 had been previously convicted of terrorist or other offences in the same EU Member State or elsewhere.

Terrorism-related travel

The number of European FTFs who have travelled to the conflict zone in Syria and Iraq is estimated to be around 5,000. In 2020, the overall volume of EU Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) (78) appeared to remain relatively stagnant, not only due to the restrictions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also as a result of the reduction in the support infrastructures of jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq.

At the time of writing the report , definitive overall EU numbers of FTFs were impossible to determine, as it has been difficult for EU Member States to verify their status or location. However, some countries were able to provide some FTF figures (regarding total numbers, returnees, detained and dead). France, for instance, one of the countries with the largest FTF contingent, identified 1451 French citizens or foreigners (aged 13 or over) who had travelled from France since 2012. At the end of 2020, 254 French citizens or residents were arrested in Syria and Iraq (84 men, 137 women and 33 minors).

Germany became aware of more than 1070 German individuals who travelled to Iraq or Syria, and nearly half of them joined IS, al-Qaeda-affiliated groups or other terrorist groups, and participated in fighting or supported them in other ways. More than half of those who travelled had German citizenship. Approximately a quarter were women. Roughly a third returned to Germany. More than 260 persons died in Iraq or Syria.

No FTFs travelled to conflict zones from Italy in 2020, and only one returned. Since 2011, 146 individuals (132 males and 14 females) with connections to Italy joined armed groups in Syria and Iraq. 53 of them were dead; the fate of 61 was uncertain; and 32 had travelled back to Europe (10 currently in Italy). The Netherlands stated that their figures for terrorist travelers remained practically unaltered in 2020: approximately 305 individuals had travelled to Syria and Iraq. Around 100 of these were killed; and 60 had returned to the Netherlands.

Belgium stated that 288 Belgian FTFs had been located in the Syria/Iraq conflict zone since the fall of Baghuz (the last IS stronghold in Syria) in 2019. However, as of late 2020, many of them—mainly men—were believed to have died, although 134 were potentially still alive. Austria had identified 334 individuals (257 men and 77 women), who either intended to travel to, or had travelled to, or returned from conflict zones. 104 of them were still in the conflict area and 95 had returned to Austria.

Sweden estimated that approximately 100 adults and a number of children remain in the conflict areas or neighboring areas, and that some of these had been detained. In 2020, Sweden had no information indicating that any individuals travelled to a conflict zone, but it did have a small number of returnees. Denmark assessed that at least 159 people from Denmark had gone to Syria or Iraq to join militant groups since the summer of 2012. At the time of writing the TE-SAT report, almost half of them had returned to Denmark or other European countries. Around one third of the total number of travelers died in the conflict zone.